8. Fun and Games

There were no organized sports for kids. So we played in pickup games. Sometimes, we played baseball or football with as few as four on a side. One of the advantages of that time, and that place, was that we could go anywhere in town or in the nearby woods. There were no busy highways to cross and nobody worried that a kid would be abducted or molested. So we were free to roam. In summer, a kid could play literally from sunrise to sunset, without causing undue worry for parents. And that’s what we did, making it up as we went along.

Spring

Spring was the time for kites and balsa airplanes and, above all, baseball. We’d start in March, which was pretty windy in Derry, with our kites. They were the standard diamond shape – no fancy box kites or dragons for us. We collected kite string as though it were gold. I remember accumulating what I thought was about 2,000 feet of twine wrapped around a cut-off broom handle. I ran it all out a time or two, but it sure was a chore reeling the kite in. So much so that I finally built a reel of sorts, using scraps of wood, a broom handle, and a piece of bent metal for a handle. It worked, but not much better than winding by hand. Kite repair was a necessary skill, since we kids didn’t have enough money to throw them away and buy new ones. So we needed to be handy with tape (“borrowed” from Grandma’s cupboard) to repair the paper covering and glue, tape, and string to repair the sticks.

In April, the balsa gliders appeared in Vitale’s variety store, across the street from Pap’s barber shop. By that time, the March winds had gone, so flying fragile gliders was reasonable. We’d gather in someone’s yard or in the street, two or three or six of us competing to see who had the longest flight or the best tricks. As with kites, it was necessary to be good at airplane repair. Otherwise, the inevitable crashes would have put a quick end to airplane flying.

But the most important event of spring was the start of the baseball season. We’d race home from school, change clothes, and gather for a game. We’d play either baseball or softball, depending on the size of field we were using. You see, Derry had no parks and only a couple of ball fields, none of them near our neighborhood. So we played on nearby vacant lots. There was one on Short Street, behind John Gruebel’s house, one on First Avenue, a block up from Grandma Heacox’s house, and another on Second Avenue, just west of Park Street. The vacant lots all were long and narrow, so the playing fields were a bit odd. At the field on First Avenue, right field was actually in Mastrorocco’s yard. On Second Avenue, right field was in Ziegler’s orchard, behind a high fence. On Short Street, right field was below a four-foot stone wall. In each case, hitting it to right field was an out for right-handers and a single for left-handers. Broken windows were a problem, since there were windows within range at each of our “ball parks.” On First Avenue, we had Mastrorocco’s house in foul territory in right, and Souder’s in left. On Short Street, it was Battaglia’s house in foul territory in left, and the VFW in straightaway center. On Second Avenue, it was Rupert’s house down the third base line. Broken windows were inevitable, and we usually just ‘fessed up when they happened. After all, in Derry, everyone knew you, so there was no hope of getting away with anything so obvious.

Usually, we had far less than a full complement of players, so the team at bat supplied the catcher and there was no stealing allowed. If we didn't even have enough for that, we'd play "21," a game in which a batter would hit balls to the rest of us. You got one point for fielding a ground ball, 3 for a first bounce, and 5 for a fly ball. If you booted it, the points were deducted from your score. When someone reached 21, he got to bat. It wasn't until I was 11 that Little League came to town. Unfortunately, the day after my birthday, I had fallen out of a tree at my cousin Sandy Heacox's house and knocked a chip off my right elbow. So I had my arm in a sling and spent part of May and all of June restricted to reading and playing games (even hopscotch) with Judy. I even got so desperate as to learn to crochet, producing some small rugs for Mom and Grandma. When I was allowed to play ball, I only got to play in a couple of games. That was the only year we had Little League when I was in the age range.

Equipment was often in short supply. We’d use a baseball as long as we could, since most of us only got a new one as a birthday gift. When the cover began to come loose, we’d put a strip of friction tape around it. This progressed until the entire ball was covered with friction tape, sometimes without the horsehide cover. Bats were even more valuable. They were wooden and cost more than baseballs. When they cracked, we wound the handles with friction tape to hold them together and deaden the vibration of the crack. Bases were whatever happened to be around, most often large rocks. The field was whatever shape the vacant lot dictated.

Not everyone had a glove, so we shared them as necessary. When I was six or seven, Dad spent the huge sum of eight dollars for a new baseball glove for me. It was a “Trapper” first baseman’s mitt and was huge for a kid my size, but I was so proud of it. I remember I had to be careful, since a hard-hit ball would tear it off my too-small hand. That was the start of a long “career” as a first baseman. I used that glove for a long time, patching it, replacing the stitching, oiling it carefully every spring and a few times in between. To my amazement, someone stole it at a softball game in Derry, when I was in college.

I spent many an hour practicing my fielding by bouncing an old ball against the concrete step in front of the porch. If I hit the sidewalk first, then the step, I could get a line drive or pop-up. If I hit the step first, the result was a ground ball. Crude, but effective.

Summer

Summertime meant freedom. I’d leave home after breakfast, heading for Grandma’s to play with my friends. It was usually Grandma who fixed lunch and, more often than not, dinner. I spent the entire day in that neighborhood, until Mom called me for dinner from Grandma’s front porch. Even then, I was reluctant. She’d start out calling “Curtie” (everyone called me that), and proceed through “Curtis” to “Curtis Heacox, you get home!” That’s when I knew it was time to move.

When I think of summer in Derry, I remember it as hot. Looking up the street toward the setting sun, the glare could be terrific and the pavement shimmered with the heat. The light had a metallic quality to it, sort of like shiny brass. When it was too hot for baseball, we had a variety of other things to do. Often, we’d just sit in the shade and talk. We’d wrestle a bit, but not enough to overheat. Occasionally, one of us might have a nickel to buy a bottle of pop, which we all shared. “Shared” meant that everyone got a sip and the owner got the rest. Still, that was pretty generous. Often, we’d go scavenging for empty bottles to return to the store for the deposit, two cents each. Another favorite pastime on hot days was walking in the woods south of town. It was cool and dark there, a welcome relief from the summer sun. We’d hike a couple of miles up to the “water dams,” small reservoirs that, strictly speaking, were off limits as part of the town’s water supply. But no one paid any attention to that. We’d sit on a large, flat boulder and toss stones into the water. Occasionally, someone would bring along a home-made boat, but mostly we just sat. If we were really ambitious, we might hike another couple of miles to the “high rocks,” a cliff that was maybe fifty feet high. From there, you could see a corner of Derry and, on a clear day, part of Latrobe. Later, when I was a Boy Scout, we’d camp in those same woods. It was, and is, beautiful country.

I also spent many hot afternoons reading on Grandma’s front porch. The Hardy Boys, Zane Grey, Boys’ Life magazine, Popular Mechanics, and comic books all got plenty of use. And, if it was really hot, there was the cellar, where I could work on my projects, usually something for my prized Lionel train. I built cars, water tanks, buildings, and trees there in the cool cellar, squirreling them away until I could bring everything out for Christmas.

I always loved thunderstorms. I’d sit on the swing on Grandma’s front porch, watching the first few drops and smelling the unforgettable odor of rain on hot pavement. Often, the rain came off the ridge in waves, pounding and splashing on the street. When the thunder and lightning got too intense, Grandma would call for me to come in, but I’d always linger for a few minutes. If there wasn’t any lightning, we’d put on bathing suits and play in the rain, building dams in the gutters, then watching to see how long it would take for the water to wash them away. If the rain was particularly heavy, we’d venture upstreet to watch McGee’s Run rushing through its concrete channel across the street from Murray’s. The channel was about fifteen feet across and five feet deep, and the stream usually occupied three or four feet, an inch deep, in the center. But around 1950, we had a particularly heavy storm and the Run filled the channel almost to the brim, deeper than anyone had ever seen it. The north side of town, across the bridge, was low ground and sustained considerable damage. Our side was higher and escaped. It sure was exciting, though.

Then there was green apple season. We'd "borrow" a salt shaker from someone's kitchen, find an apple tree, and eat salted green apples, often leading to the dreaded attack of "collywobbles" if we ate too many. There was also a plant, whose name I can't remember, that had a hollow stem just right for a pea-shooter. Of course, since we had little money, we used green chokecherries for ammunition.

The highlights of the summer were the two carnivals. The Fire Department’s Drum and Bugle Corps and the American Legion each held a street fair to raise funds. The Drum and Bugle Corp had theirs on Second Avenue between Ligonier and Chestnut Streets, and the Legion had theirs a block further west, blocking off the street. The carnival ran Monday through Saturday and we kids went every night. Since everyone you knew was there, it was the social center of Derry for the whole week. Wednesday evening, there always was a big parade. It would start on the other side of the bridge, come up and over, and end at the carnival location. In those days, every town and school had a drum and bugle corps or a marching band, so there were plenty of musical units in the parade. And every fire department in the area would send their best trucks. They were great parades.

At the carnival, there would be a few kiddy rides, the usual cars or airplanes going around in a circle. There was always a bingo stand, using dried corn for markers and paying off in cash. I spent many an hour sitting there with Grandma. If you strolled past the bingo stand, you’d find the chuck-a-luck and keno games. Chuck-a-luck was a wheel of fortune game, each slot containing a combination of three dice. You’d bet on a number, the wheel would spin, and you’d be paid according to how many of your number showed on the dice. Triple one and triple six were the house numbers. In Keno, you’d bet on a number, then someone would roll a ball up a ramp, where it would settle in a numbered hole. Those who had bet on that number would win. There was plenty of food. There was a stand, run by the carnival company, that sold popcorn and cotton candy. But the most popular stand was the one run by the host organization. It featured hamburgers, French fries, and pop, but the dish of choice was a hot dog with sauerkraut. It cost a quarter, as I recall. One of my favorite activities was pitching pennies at a platform of orange or gold dishes. If your penny stayed in a dish, you won it. I brought home my share of orange dishes for Mom and Grandma, which they patiently put away, probably wishing I’d find something else to do. Some of that glassware would be worth money today.

Then there were the two summer holidays, Memorial Day (usually called Decoration Day) and the Fourth of July. We had a sizable parade for each of them. We kids would save our pennies to buy red, white, and blue crepe paper with which to decorate our bikes. We’d weave the strips of paper through the spokes, wrap it around the crossbars, and let it stream from the handlebars and rear fender. If we were really lucky, we’d have a small flag or two to tape to the handlebars. Then we’d ride in the parade, being careful not to go too fast. If we did, the centrifugal force on the wheels would make our carefully woven crepe paper slide into a tangled mess against the outside rim. The parade would start at the Municipal Building and march across the bridge to Coles Cemetery, where there’d be a short service, followed by the playing of “Taps” and a rifle salute. Then we’d go back across the bridge to the Municipal Building and the war memorial next to it, where we’d do it all again, with the addition of speeches by the local politicians. It was a bit hokey by today’s standards, but you have to remember that a lot of the names on the memorial were still fresh, World War II having ended just a few years before, and new ones were being added in the Korean War, which was going on at the time.

Fall

September meant school, and I must admit that I didn’t mind it too much. First of all, I was always curious and the beginning of school meant a whole new set of textbooks. I’d start with the science book, followed by math, history, etc., and read them all cover to cover, usually by the end of the second week of school. There were so many new things to learn. Of course, the rest of the year was a bit of an anticlimax. Fortunately, most of my teachers were understanding and were willing to spend extra time giving me advanced work or suggesting additional reading.

September

also meant football season. We played our pickup games without equipment, since

only a few of us had helmets or pads. Sometimes we played touch, but often it

was tackle. If we didn't have enough players for a game, we played "free for

all," a game in which someone would toss the ball in the air and whoever caught

it became the runner, with the rest of us chasing, and eventually tackling,

him. But, more importantly, the season also began for the high school team. The

football field was atop a steep hill

above Fourth Avenue, several blocks from the high school. It always seemed a

bit odd to see the players of both teams, walking from the high school, where

the locker rooms were, to the field, then trudging back after the game. Usually,

we were underdogs, since we had fewer than 180 students in grades nine through

twelve, 35 of whom would turn out for the team. The minimum weight was 130

pounds. I remember a halfback named “Fuzzy” Albaugh, who was a couple of years

older than I. Fuzzy’s normal weight was less than 125, but he was determined to

play football. So, each year on weigh-in day, you could see Fuzzy sitting in

front of Mastrorocco’s Supermarket, eating bananas and guzzling water so that

he could weigh in at 131. Fuzzy was a pretty good runner and a ferocious

cornerback. Most of Derry turned out for the games, many walking up the steep

hill to the field to cheer the team on. It was always quite an occasion.

September

also meant football season. We played our pickup games without equipment, since

only a few of us had helmets or pads. Sometimes we played touch, but often it

was tackle. If we didn't have enough players for a game, we played "free for

all," a game in which someone would toss the ball in the air and whoever caught

it became the runner, with the rest of us chasing, and eventually tackling,

him. But, more importantly, the season also began for the high school team. The

football field was atop a steep hill

above Fourth Avenue, several blocks from the high school. It always seemed a

bit odd to see the players of both teams, walking from the high school, where

the locker rooms were, to the field, then trudging back after the game. Usually,

we were underdogs, since we had fewer than 180 students in grades nine through

twelve, 35 of whom would turn out for the team. The minimum weight was 130

pounds. I remember a halfback named “Fuzzy” Albaugh, who was a couple of years

older than I. Fuzzy’s normal weight was less than 125, but he was determined to

play football. So, each year on weigh-in day, you could see Fuzzy sitting in

front of Mastrorocco’s Supermarket, eating bananas and guzzling water so that

he could weigh in at 131. Fuzzy was a pretty good runner and a ferocious

cornerback. Most of Derry turned out for the games, many walking up the steep

hill to the field to cheer the team on. It was always quite an occasion.

Throughout grade school, I was a little above average in size. One of the teachers organized an after-school basketball program for seventh and eighth grade boys and I was pretty good. But when we returned from summer vacation to start high school, I found to my dismay that everyone else had grown several inches and twenty pounds, while I had not. I never caught up with them. So, for example, I weighed 110 pounds until my senior year, when I got up to 125, so I never even got the chance to play football. And I was at such a disadvantage in size and strength that I wasn’t very competitive at basketball, either. I tried for two years, but finally gave up, becoming the team statistician my junior year. At least I got to go to away games on the team bus.

When I was a sophomore in high school, I had biology class. The first assignment was to collect and identify fifty insects. Well, I’ll tell you that John Gruebel and I got fired up for that. Off we went to the drug store for small bottles of carbon tetrachloride to kill the insects we caught. Then we made butterfly nets out of broom handles, coat hangers, and old curtains. Grandma sewed my net together. I’m told we were quite a sight, running through the neighborhood with our nets streaming out behind us. Grandma said later that she’d never laughed so hard as when she saw us go by the kitchen window. But we got our fifty bugs. Later in the year, it was fifty leaves and, in the spring, fifty wild flowers. John and I had a ball in that class.

I had Mrs. Tovo for plane geometry and Latin. She was a lovely lady, but just a bit bewildered most of the time. In both her classes, Jack Blair and I had friendly competitions to see who could prove the most extra-credit theorems or translate the most extra-credit Latin selections. Mrs. Tovo was willing to do the extra work to grade them for us.

As a junior, I had an unspoken agreement with my English teacher, Mrs. McKelvey, that I could sit in the back of the room and read. She wouldn’t call on me unless I was looking at her. She paid me a great compliment when she said one day, “Curtis, I know that you know this stuff and it would be boring for you to go over it again. You’ll get a lot more out of reading these books.” She was my all-time favorite teacher.

Pat Bucci was another of my favorites. He coached the high school football and basketball teams, as well as teaching algebra, chemistry, and physics. The boys all called him Pat, never Mr. Bucci. He was one of those teachers who are able to treat high school students like adults and to laugh with them, without ever losing control of his team or his class. He never hesitated to cuss out the team or apply discipline in class. I well remember the day he sailed an eraser past my ear and off the blackboard behind me, because I was talking in his algebra class. But he accepted no excuses and helped teach us all to be responsible for our actions.

As the days got shorter, fall became the time for hide-and-seek games after supper. We played a variety of them. There was the usual game, which we called “hidey-go-seek.” Then there was “kick the can,” in which one of us would kick a tin can as hard as he could and we would all hide while “it” retrieved the can and brought it back to home base. There also was a variant called “kick the stick,” for those times when we didn’t have a can. As we grew older, hide-and-seek evolved into a team game, which we called simply “Chase.” We’d choose up sides, agree on boundaries, usually about two square blocks, then one team would hide and the other would wait an interval, then chase them. There was no home base and members of the hiding team had to be caught and tagged. It could take all evening.

In general, the railroad tracks were out of bounds to kids, at least in the eyes of their parents. I well remember the night I was late for supper. We still lived above Foster’s, so I was less than nine years old. My Dad finally found me playing hide-and-seek beneath a boxcar on a railroad siding. While I didn’t get the expected spanking, he did literally drag me home and send me to bed without supper. It didn’t keep me off the tracks, but I was a lot more careful about it.

Derry had two elementary schools. Second Ward School was just a block from Pap and Grandma, while Third Ward was located across the bridge, near the Methodist Church. Each school had grades 1 through 6. Grades 7 and 8 were on the second floor of the high school building on Fourth Avenue. Each elementary school had a Safety Patrol, a group of sixth grade boys charged with guarding the intersections near the school both morning and afternoon, while the younger kids crossed the street. Since everyone walked to school — there were no school buses – the school day was the same for all classes. The boys on the Safety Patrol had cool webbed belts that went over the shoulder, across the chest, and joined with a belt at the waist. They had shiny, official-looking badges that said “Safety Patrol.” And they had flags, wooden poles, about seven feet long, with red flags at the end. When the leader blew his whistle, they’d lower the flags, blocking the traffic lanes and stopping traffic until the kids had crossed. In 1951, when I was to start sixth grade, I had been designated captain of the Safety patrol. Captain! I was so excited I could hardly tell my parents. In August, I developed a stomach ache. Mom and Dad took me to see Dr. Blair, who thought it might be appendicitis, although the pain was on the wrong side. He sent us to Latrobe Hospital to see Dr. John Hamill, one of the best surgeons in the county. He, too, was puzzled by the location of the pain, but felt surgery would be a good idea. After some discussion, he looked at me and asked me what I wanted to do. Having listened to all the potentially serious consequences, I decided surgery was the thing to do. That turned out to be the right choice. They made a midline incision that was twice as long as usual and found that my appendix was about to burst. It had actually been moved along with a section of my large intestine, which was why the pain was in the wrong place. I spent several days in the hospital, then returned home. A couple of days later, I had severe stomach pains and went back to the hospital for two more days. By the time I recovered, school had started, Richie Graham was captain of the Safety Patrol, and I was just a substitute. I was heartbroken.

Winter

If summer in Derry was the color of brass, winter was more like lead, or at best, pewter. The average temperature in January, the coldest month, was about thirty degrees. It snowed quite a bit, but rarely lasted more than a couple of days. Most of the time, the town was either ankle-deep in slush and cinders or just a dismal gray.

But when it snowed in Derry in the fifties, it was a kid’s dream. The town put out sawhorses at all the intersections on the good sled-riding streets (nobody ever said “sledding”), to warn the motorists that kids on sleds could zip through the intersection at any time. Of course, there weren’t as many cars then, but it still was quite a concession to us kids. I don’t remember anyone being hurt by a car. Trees yes, cars no. Also, they only spread cinders on half the street, leaving the other half slippery for the sleds. When we lived in the old house at 714 East First Avenue, the favorite hill was East Street, where you could start at Third Avenue and sled two full blocks down a pretty steep hill. We usually built a jump on the far side of First Avenue, where there was a natural dip to help. That shot us several feet into soft snow, since the block between First Avenue and Railroad Street was never plowed. (I recently stood at the top of that hill with Peter, looking down at First Avenue and wondering how we ever survived a thousand trips down!)

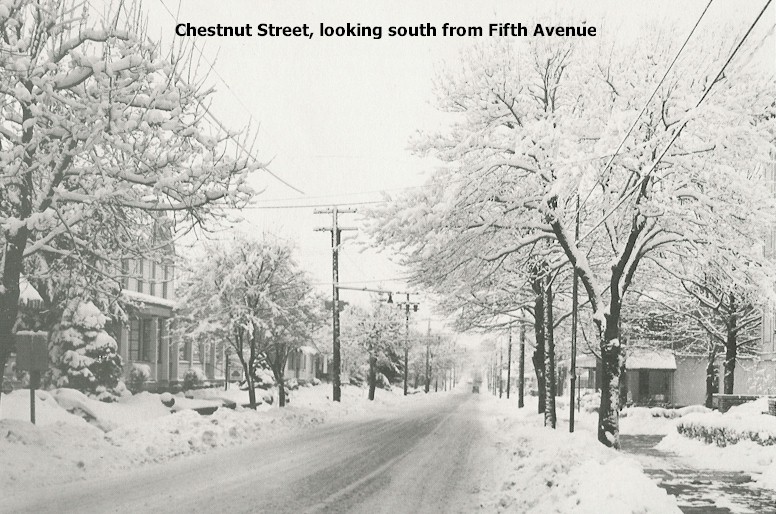

When

we lived at 124 East First Avenue, Rhodes’s Hill was closer. It wasn’t as steep

as East Street, but it had other features. You could start on Ligonier Street,

half a block above Third Avenue, then make the turn onto Third, heading for

Chestnut Street. Or you could start a block east of Ligonier Street on Third

and take the straight route. Finally, those who were brave enough, could start

on High Street, which was pretty steep, try to make the turn onto Third,

then ride a block and a half to the foot of the hill. For safety, there was a

rise to Chestnut Street that kept us out of that busy street.

When

we lived at 124 East First Avenue, Rhodes’s Hill was closer. It wasn’t as steep

as East Street, but it had other features. You could start on Ligonier Street,

half a block above Third Avenue, then make the turn onto Third, heading for

Chestnut Street. Or you could start a block east of Ligonier Street on Third

and take the straight route. Finally, those who were brave enough, could start

on High Street, which was pretty steep, try to make the turn onto Third,

then ride a block and a half to the foot of the hill. For safety, there was a

rise to Chestnut Street that kept us out of that busy street.

When I was a bit older, we sometimes trudged up the ridge road that led up Chestnut Ridge. We’d hike until we got tired, then ride our sleds down that narrow, winding dirt road. You could get up a pretty good head of steam on those hills, making the ride down a bit chancy. More than that, we weren’t allowed to sled on that road, so any cars were not looking out for us. But at that age, who worried? Then came the night Barry Hall missed a high-speed turn in the dark and slammed into a tree. Luckily, he hit the tree runners first and escaped with just a scare and a bent sled. After that, the Ridge Road lost some of its appeal.

Anyway, it was a good day if it was snowing as I made my way home from school, and it looked like there’d be enough to sled on after supper. If so, I’d grab my sled and head up Ligonier Street. The traffic usually had packed the snow nicely and made it slippery. I can close my eyes and remember those evenings. I remember big snowflakes falling like feathers through the glow of the streetlights, coating the ground like a blanket. The trees and bushes became magical sculptures in black and white. In the twilight, the snow always seemed to be blue, verging on purple. The falling snow muffled sounds in a curious way. You could hear the shouts of your friends quite clearly, but it was as if the edges had been softened, mellowed. It was a magical time, covering the industrial dirt in a clean white blanket. Winter in Derry was rarely really cold, so we could enjoy ourselves as long as we wanted, or as long as our parents would let us. It would be a couple of hours before I would head home, tired and a bit wet, but content.

When I was in sixth grade, Tom Wingard and a few others started a basketball league for us kids. Tom was an old family friend whose family lived just across the street from Pap and Grandma. He also taught me civics and history when I was in high school. Anyway, this was an after-school league in the high-school gym. It was very low-key and parents didn't attend. We concentrated on the fundamentals, mostly, with games, but no formal teams. That lasted through eighth grade and was great fun. At the same time, practices for the high school team were open to anyone who wanted to attend. I spent many a Saturday in the gym watching my heroes. First, the team would practice and scrimmage. Then, most Saturdays, any alumni who were around would play against the team. Those were some spirited games! Finally, the team would shower and depart, leaving the gym to us "gym rats". We played pickup games, had long-shot contests. Pat Bucci, the coach, would return about 2:30 PM, kick us out, and lock up.