6. And Then We Were Three

We were just an average family by Derry’s standards, at least until I was 12 and Judy was 10. Then, one November evening, while Mom was off somewhere with Grandma, Dad sat down in our brown, threadbare easy chair and put Judy on one arm of the chair and me on the other. Then he told us that he didn’t love Mom anymore, that he’d found someone else. As it turned out, “someone else” was an eighteen-year-old blonde named Thelma (Dad was 37 at the time). Later, we were surprised to find that she had borne him a daughter named Janet. Anyway, we were shocked, bewildered, and very frightened. And Mom was absolutely furious when she returned and found out that he’d told us. So began the disintegration of our family. The next nine or ten months were very difficult, although Judy and I were too young to understand fully. Mom, as usual, bore the brunt for us.

As things went on their downward spiral, Mom and Dad fought as they never had. She was trying desperately to keep us together; he was trying to get away. Once, Mom got out a suitcase, threw some clothes in it, and walked out. After considerable crying and wailing, Dad put us in the car and went after her. We found her several blocks away on Second Avenue, walking along in a chill wind, tears running down her face. It was one of the scariest days of my life. But scarier still was a day the following spring. Dad was playing “You Belong to Me,” by Jo Stafford, on the phonograph. It was his and Thelma’s song, and Mom lost it. She grabbed the record and smashed it on the floor. By the time the shouting ended, they had broken nearly every record in the house, while Judy and I cowered on the couch. Finally, Dad pushed Mom and she fell. That was too much for me and I jumped up and hit Dad as hard as I could. In a sort of reflex, he hit me backhanded and sent me flying across the room. I remember that there was a shocked silence, then the fight was over. As far as I can recall, it was the only time my father ever hit me.

Early in the summer, Dad finally moved out and, after spending some time sleeping in his parked car by the post office, got a room in town. A short time later, we moved out of that big old house and into a two-bedroom apartment on the second floor above Murray’s restaurant. It was a bit strange, living just around the corner from Dad, but we got used to it. Our landlord, J. Monroe Murray, and his wife had the apartment next to us, and Harry and Mildred Baker were across the hall. Mom and Judy shared the larger bedroom, leaving me with a room of my own, at least at night.

The apartment overlooked the railroad bridge that linked the two halves of town. Mildred frequently came over to visit and she and Mom sat at the living room window on two small folding chairs, part of a child’s card table set that Judy had been given for Christmas some years before. With their cups of coffee and an ashtray, they sat and smoked and watched the traffic going back and forth over the bridge. Since this was the only reasonable way to travel across town, most of the population crossed it at least once a day, so there was plenty to see. This was a year-round activity, though in summer they often adjourned to Mildred’s porch, also overlooking the bridge. They could spend hours speculating on why Mr. Smith made so many trips across the bridge and wasn’t that an awful dress what’s-her-name had on today? They laughed and joked, all the time watching for Millie’s husband Harry, better known as “Pup,” to come home from work at the Westinghouse. Seeing him walking across the bridge was her signal to head for home and put supper on the table. Sometimes I think Millie was a lifeline for Mom at the most difficult time of her life. Her friendship and good humor never failed.

Mom tried working as a waitress in the restaurant downstairs, but the job made her very nervous, so she got a job at the G. C. Murphy five-and-ten-cent store in Latrobe. Unfortunately, our rent was more than half her month’s pay. After taking out bus fare, there wasn’t much left, so we ate most of our meals with Pap and Grandma. When we did eat at home, it was likely to be hot dogs and baked beans or potato soup or macaroni and cheese. And it was Pap’s account at Petrarca’s men’s store that clothed me through high school and much of college.

I remember those years as a happy time. There was an “us against the world” feeling, and we worked together to keep things going. Monday was washday and Pap’s day off, so he and Grandma did their wash and ours together. Each Sunday evening, Mom would pack our dirty clothes into a peach basket that was about two feet in diameter and I would carry it to Grandma’s. Monday evening, I’d carry the same basket, now full of clean clothes, back home. Fridays, after school, Judy and I would clean the apartment, dusting, vacuuming (known as “running the sweeper” in Derry-ese), and generally tidying the place.

I guess it should be said that Judy seems to have a different view of those years. She seems to think her childhood was terrible, but I don’t know why. I think my memories are reasonably accurate, but she saw things differently, I guess. Certainly, Dad’s leaving affected her differently, and more profoundly, than it did me. Maybe that’s the reason.

Anyway, Mom was our hero. She managed to keep us going for years after she and Dad split up. She held down a job, kept the apartment going, with some help from Judy and me, and kept us afloat, with a lot of help from Pap and Grandma. Mom was tenacious. She just didn’t know how to give up, even when things looked most bleak. We could have gone to live with Pap and Grandma, but Mom insisted that we have our own place. She did it all with considerable grace and good humor, though, late at night, the tears sometimes came. But we didn’t dwell on that.

Meanwhile, Dad moved to Warren, Ohio. He had a buddy from

his Kennametal days who lived there. He worked for Republic Steel for the next

few years and even helped us out financially, although not much. He was in and

out of our lives throughout my teen-age years, coming to visit from time to

time. Though he didn't have much money, he always managed to come up with a car, often

borrowed from a friendly used-car dealer. On one of his visits when I was 14, he gave

me my first driving lessons. We went to Burd's Crossing, just west of town along

the railroad tracks. Near there was a sizable open space of hard-packed cinders,

used by the railroad to store bulky items, such as ties and rails. We spent an

hour or so in his '50 Ford as he tried to teach me the secrets of a three-speed

transmission with column-mounted shifter. But when it came time for me to take my

driver's test, it was Uncle Jim who took me to Greensburg.

Meanwhile, Dad moved to Warren, Ohio. He had a buddy from

his Kennametal days who lived there. He worked for Republic Steel for the next

few years and even helped us out financially, although not much. He was in and

out of our lives throughout my teen-age years, coming to visit from time to

time. Though he didn't have much money, he always managed to come up with a car, often

borrowed from a friendly used-car dealer. On one of his visits when I was 14, he gave

me my first driving lessons. We went to Burd's Crossing, just west of town along

the railroad tracks. Near there was a sizable open space of hard-packed cinders,

used by the railroad to store bulky items, such as ties and rails. We spent an

hour or so in his '50 Ford as he tried to teach me the secrets of a three-speed

transmission with column-mounted shifter. But when it came time for me to take my

driver's test, it was Uncle Jim who took me to Greensburg.

Later, when I had my license, Dad showed up for a winter visit driving a Hudson that had seen better days. He let me drive it that evening to go out with my friends. Coming down a hill in West Derry, I skidded on a patch of ice, slid off the road sideways, took out a mailbox, and came to rest against a telephone pole. Fortunately, I wasn't going very fast, so there was just a dent in the door. Dad actually got the dealer to apologize because "the brakes weren't very good."

Occasionally, Judy and I went to visit him in Niles, Ohio, near Warren.

He was rooming with a very nice couple named Gus and Harriet Hilliard, who

graciously provided an extra bedroom for Judy. It was a strange situation. I

particularly remember one winter visit. Dad’s brother Lewis, usually called

Duck for no reason known to me, picked us up and drove us home. Now, Uncle Duck

drove like a madman. As we exited the turnpike at Monroeville, he lost control

on a patch of ice, doing a neat 360. Lucky for us, there were no cars coming

and he was able to keep it on the road. I remember Dad spinning around in the

front seat and reaching back in an effort to protect us. He loved us, I guess.

He just had a hard time growing up and taking responsibility.

Occasionally, Judy and I went to visit him in Niles, Ohio, near Warren.

He was rooming with a very nice couple named Gus and Harriet Hilliard, who

graciously provided an extra bedroom for Judy. It was a strange situation. I

particularly remember one winter visit. Dad’s brother Lewis, usually called

Duck for no reason known to me, picked us up and drove us home. Now, Uncle Duck

drove like a madman. As we exited the turnpike at Monroeville, he lost control

on a patch of ice, doing a neat 360. Lucky for us, there were no cars coming

and he was able to keep it on the road. I remember Dad spinning around in the

front seat and reaching back in an effort to protect us. He loved us, I guess.

He just had a hard time growing up and taking responsibility.

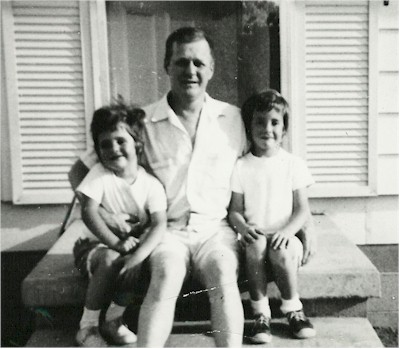

I got along well with Dad, better than Judy did. When I was a freshman in college, he had a heart attack. Mom, Judy, and I went to Warren to see him in the hospital. I remember a woman leaving his room just as we arrived. It was Malvina, a remarkable woman with whom he was living. Somehow, Mal was able to cope with Dad and make him settle down. They had three daughters, Stephanie, Cindy, and Alison. The picture shows him with Stephanie and Cindy. The one at left is Malvina. Unfortunately, I lost track of them after Dad died. Finally, around 1960, Mom relented and agreed to a divorce and Dad finally married Mal. I stayed in touch with Dad until he died in January, 1968. Nancy and I would stop in Warren for an hour or two on our way to or from Derry. We’d have a cup of coffee and talk. It seemed to please Dad. I last saw him just after Christmas in 1967. We stopped for a visit and he was able to hold his first grandchild, Chris, for the first and only time. He died of a massive heart attack less than a month later. He was 52.