1. Derry

Where to begin? I guess the best starting point is Derry, itself. We are all products of many influences. Our parents provide the genes. They are also the first, and most important, of the environmental influences. Later, our grandparents, siblings, friends, acquaintances, and even enemies will add their distinctive impacts. In the world in which I grew up, most people stayed home most, or all, of their lives. My parents and my grandparents on both sides, as well as many of my aunts, uncles, and cousins, lived out their lives within a few miles of their birthplaces. So, in a very real sense, those born in the forties or earlier, were really products of their home towns. Sadly, that world doesn’t exist any more. I’d like to tell you what it was like.

I was born Harry Curtis Heacox, Jr., son of Harry, Sr. and Mary Alice Bollinger

Heacox. It has been said

that much of life is in the timing. I was born May 23, 1940, at the tag end of

the Great Depression and just before the start of World War II. Those two

cataclysms had a great deal to do with the attitudes of my parents and

grandparents. The hardship of the depression made everyone conscious of the value

of money and the merits of being thrifty. In our house, and most other houses

in Derry, things were mended, not thrown away. “Making do” was an art form. I

remember my grandmother removing the frayed collars from my shirts, turning

them around, and reattaching them, thus saving the cost of a new shirt. And Mom

spent many an evening darning holes in my socks.

I was born Harry Curtis Heacox, Jr., son of Harry, Sr. and Mary Alice Bollinger

Heacox. It has been said

that much of life is in the timing. I was born May 23, 1940, at the tag end of

the Great Depression and just before the start of World War II. Those two

cataclysms had a great deal to do with the attitudes of my parents and

grandparents. The hardship of the depression made everyone conscious of the value

of money and the merits of being thrifty. In our house, and most other houses

in Derry, things were mended, not thrown away. “Making do” was an art form. I

remember my grandmother removing the frayed collars from my shirts, turning

them around, and reattaching them, thus saving the cost of a new shirt. And Mom

spent many an evening darning holes in my socks.

I remember, too, my mother’s fear that my dad would be drafted during the war. He had served in the army in Panama before the war, and he had first one, then two children. In addition, he worked in a war-critical industry at Kennametal, in Latrobe. But, late in the war, that didn’t necessarily protect him from the draft. And I remember my parents’ friends and Aunt Andrea’s husband, Tom, coming to visit in their uniforms. They certainly were impressive to a five-year-old boy.

Derry, like most towns in western Pennsylvania, was (and still is) a working-class town. I’ve provided a map showing Derry in the fifties, as I remember it. Aside from two doctors, a lawyer, a couple of dentists, some successful businessmen, and a few frugal teachers, the people of Derry got by on working man’s wages. There was the railroad, the Westinghouse insulator works, a few poor coal mines, and several metal works in neighboring Latrobe. They provided much of the income for the townspeople. In addition, few women worked and most families were dependent on the husband’s income.

We had large Italian and Polish communities, as well as many of Hungarian, Ukrainian, and Irish descent. I don’t recall that there were any Jews or African-Americans in town. We had the usual selection of churches, of which the Catholic Church was the largest, by virtue of the afore-mentioned communities. Pap and Grandma were staunch Methodists, so we went to the Methodist Church, on the other side of the bridge. Dad’s parents went to St. Paul’s Evangelical and Reformed Church on Chestnut Street. Curiously, I don’t remember ever setting foot in that church. But then, we weren’t very close to Grandpap and Grandma Heacox.

When I was a child, a car in every driveway was still years in the future, and it wasn’t easy to go five or ten miles to the supermarket. So Derry could support a full range of businesses, including two supermarkets, a drug store, a bakery, a fruit market, several neighborhood stores (the PDQs of that time), three barbers (my grandfather was one), two clothing stores, a furniture store, a hardware store, a bowling alley, a movie theater, two restaurants, two funeral homes, a downtown gas station, even a Ford dealership. In the years since, almost all have closed, leaving a single supermarket, a drug store, a video store, a newsstand, and a few other struggling businesses. But back then, you could live well without ever leaving town, which made a shopping trip to Latrobe, six miles away, something of an adventure.

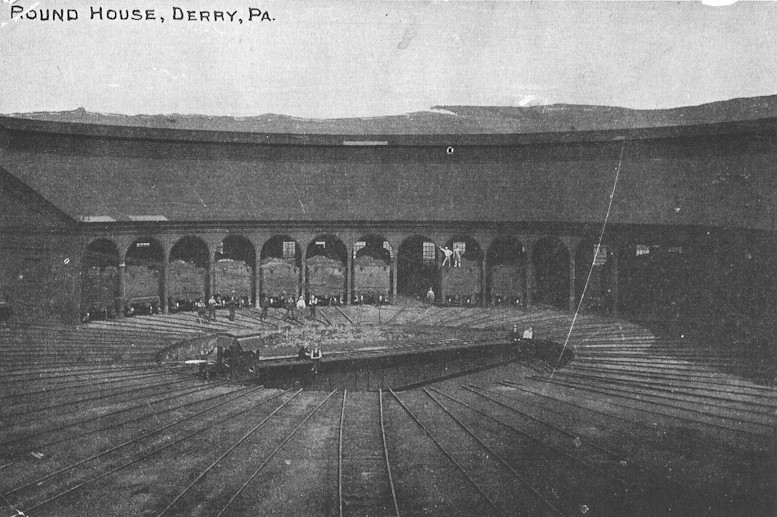

Derry

was a dirty place. The main line of the Pennsylvania Railroad ran through the

middle of town. In the forties, Derry had some significance on the railroad.

Diesel locomotives were just beginning to appear and steam locomotives still

ruled. They required extensive services and frequent stops for coal and water.

Derry was an important maintenance and refueling stop just east of Pittsburgh.

Steam locomotives were marvelous to watch, but how they could spread dirt! Most

of them burned coal, at least in Pennsylvania where coal was plentiful and

cheap, and each one trailed an enormous plume of black smoke, from which rained

soot and very fine black cinders. In the forties, I had never heard of a

clothes dryer. You dried clothes by hanging them on a clothesline, outside in

the summer and in the basement, oops, I mean the cellar, in winter. Well, my

grandmother had a finely-tuned ear for the sound of a steam engine’s whistle.

She had a first step that would have made Michael Jordan envious. She could be

out the door and have a whole yard full of wet clothes pulled down and in the

basket before that train could travel the two or three miles from Burd’s

Crossing to her house. Of course, all that coal produced mountains of ash to be

disposed of. Many roads were made of hard-packed cinders, with or without oil

to keep the dust down. In winter, the city used black cinders on the roads,

since that was much cheaper than sand. Our basketball court, behind the VFW

(Veterans of Foreign Wars), was made of hard-packed cinders. In wet weather,

we’d go home with a thick, black coating of cinders on our hands. Yes, Derry

was a dirty place.

Derry

was a dirty place. The main line of the Pennsylvania Railroad ran through the

middle of town. In the forties, Derry had some significance on the railroad.

Diesel locomotives were just beginning to appear and steam locomotives still

ruled. They required extensive services and frequent stops for coal and water.

Derry was an important maintenance and refueling stop just east of Pittsburgh.

Steam locomotives were marvelous to watch, but how they could spread dirt! Most

of them burned coal, at least in Pennsylvania where coal was plentiful and

cheap, and each one trailed an enormous plume of black smoke, from which rained

soot and very fine black cinders. In the forties, I had never heard of a

clothes dryer. You dried clothes by hanging them on a clothesline, outside in

the summer and in the basement, oops, I mean the cellar, in winter. Well, my

grandmother had a finely-tuned ear for the sound of a steam engine’s whistle.

She had a first step that would have made Michael Jordan envious. She could be

out the door and have a whole yard full of wet clothes pulled down and in the

basket before that train could travel the two or three miles from Burd’s

Crossing to her house. Of course, all that coal produced mountains of ash to be

disposed of. Many roads were made of hard-packed cinders, with or without oil

to keep the dust down. In winter, the city used black cinders on the roads,

since that was much cheaper than sand. Our basketball court, behind the VFW

(Veterans of Foreign Wars), was made of hard-packed cinders. In wet weather,

we’d go home with a thick, black coating of cinders on our hands. Yes, Derry

was a dirty place.

The major landmark in Derry was the old bridge over the railroad tracks. Starting from our side, it had a steep upward slope, on wooden trestles, to gain enough height to clear the tracks and the trains. At the top was a truss bridge stretching over the tracks. On the other side was a gentler slope downward, again on wooden trestles, but with a sharp right angle turn to the left halfway down. The roadway was narrow. There was just enough room for two school buses to pass, with about three or four inches’ clearance between their mirrors. I remember starting from our side of the bridge, straining to ride my fat-tired Scwhinn to the top, pedaling as hard as I could to start the downslope, making the corner on the far side of the bridge, coasting down to the corner at Chestnut Street at full speed. From there, I would coast down the slope on Chestnut to the corner at Third Street and finally end my ride at the Methodist Church. To think that such a ride could be made by a 12-year-old without a helmet! Later, the bridge was a test of driving ability for us kids. You had to be able to drive across it one-handed, preferably with one's right arm around one's girl friend (and remember, power steering was all but unknown).

So what didn’t we have? Well, many families, including ours, had no car. I was eight, in 1948, when we got our first car, a 1937 Studebaker 4-door sedan. It was an ugly, dull gray, but my Dad was so proud of it. Many evenings in the summer, we’d all get in the car and just go for a ride. Of course, gasoline was less than 20 cents per gallon, so it wasn’t too extravagant. And it’s startling to think that, even when I was a teenager, used car ads in the Latrobe Bulletin still mentioned whether or not the car had a radio and heater. Anyway, people took the bus to Latrobe or Greensburg and the train to Pittsburgh. But mostly people walked. We walked to work and we walked to school. We walked to the store and we walked to church. Kids, of course, rode bikes everywhere, even in the winter. When we grew older, we walked on dates. I remember many an evening walking across the bridge to pick up my girl friend and walking back across the bridge to the movie theater. After the movie, we did the same in reverse.

Every house had a front porch and they all got a lot of use. Any nice summer evening saw what seemed like half the population sitting on their porches, while the other half strolled up and down the streets, stopping to talk with their neighbors. Practically every street had sidewalks and houses were set just a few feet back, so it was easy to talk across the railing. There weren’t many mosquitoes, so you could spend hours just sitting. Grandma’s porch furniture all was painted black (remember those cinders). In the center of the porch, there was a wooden rocking chair where Pap always sat. Right next to it was a swing, hung on chains from the porch ceiling. Mom, Grandma, and Judy sat there, though it was a tight fit for three. At the opposite end, in the corner next to the door, there was a classic Adirondack chair where I always sat. I remember many an evening, sitting there and watching the fireflies blinking in Bill Shimpf’s yard, across the street. Many hot afternoons, I'd sit on the swing, idly swinging back and forth. I can still remember Grandma yelling from the kitchen, "Stop banging that swing against the house!"

People had party telephone lines. Two or four families would share a single line. Each number had its own ring, so you could tell whose call it was. You had to listen carefully to tell if the neighbors were listening to your call. And even if you were convinced they weren’t, you were pretty careful about what you said. But a private line was a great extravagance. And a long distance call was expensive. It could cost a dollar or two to call our relatives in Pittsburgh. Doesn’t sound too expensive? Well, when I was in high school, my Dad was making about $100 per week, $5,000 a year, working for Republic Steel. That was considered “good money.” Today, that call might still cost a dollar, but $20,000 per year is below the poverty line.

There were only three air conditioners in town when I was in grade school. The movie theater and the two supermarkets (actually just big grocery stores) had them. I don’t believe anyone in town had a home air conditioner. And air-conditioned cars were unheard of. In summer, window fans were a necessity, which made it interesting when a train rumbled through while you were trying to watch TV or listen to the radio. Speaking of TV, I never saw one until I was about seven years old, in 1947. That’s when they started to appear in town. People would invite their friends over to watch the tiny black and white picture. I was nine when we got our first TV.

What did we do without TV? We listened to the radio. I listened to the Pirates on Sunday afternoons in the summer, suffering with them as they “held up the rest of the league.” When there was no Sunday baseball game, Mom and Dad listened to Sammy Kaye and his Orchestra. In the evenings, we all listened to comedy shows like Jack Benny, Fred Allen, and “The Life of Riley.” We all thought those shows were hilarious. In the years since, I’ve heard recordings of some of them, but somehow, they’re not nearly as funny as they were then. I think it has a lot to do with the way the world has changed. Mom and Grandma were devoted to the soaps on the radio. They had names like “Stella Dallas,” “Lorenzo Jones and His Wife Belle,” and “Just Plain Bill, Barber of Heartville.” One of the advantages of radio was that they could listen while they did their housework. They didn’t have to watch.