10. Christmas

Then, as now, Christmas was one of the axes around which a kid’s life revolved. The presents (they were never called gifts), the music, the presents, the tree, the presents, Christmas vacation, and the presents made sure of that.

While Dad “made good money,” we were by no means even well off. Even so, Mom and Dad worked hard and did their best to give Judy and me the things we wanted for Christmas. One interesting thing was that Judy and I seemed to have a kind of subconscious awareness of our situation and rarely asked for impossible things. So our Christmas was usually a good balance between what was wanted and what could be provided. That was true for most of my friends, as well. Of course some of my friends, such as Jack Blair and John Gruebel had considerably more. But, while I remember wishing I could have things like that incredibly neat wire recorder that John’s brother had, I was usually content to visit them and play with their stuff.

I remember many Christmas incidents that can still bring a smile and a shake of the head. When I was about eight, toward the end of Christmas Day, Mom asked me if I got everything I wanted. I thought a minute, then said, “Everything except the microscope.” “Oh, my God,” she said as she jumped up, ran to the closet, and pulled out my new microscope from its hiding place at the back of the highest shelf. We won’t speculate about why an eight-year-old kid wanted a microscope. Suffice to say that it was a compromise – they thought I was too young for a chemistry set.

My favorite gifts were books. When I was young, there was always a Hardy Boys mystery or two under the tree for me. Later, Zane Grey westerns were the thing. To this day, a book or a Barnes and Noble gift certificate is just right. Almost as important as books were things I could build or build with. An Erector set, Lincoln Logs, an electric drill were all outstanding presents. I made a habit of taking apart any toy that could be disassembled, with about a fifty percent success rate in re-assembling them. Mom would get pretty mad about that, but eventually came to accept it as just another quirk of mine. I particularly remember a quiz book with a pen that would light up if you touched it to a dot next to the correct answer. It was clearly just a flashlight, but I had to take it apart anyway. When I couldn’t get the bulb out, I tried some chewing gum on the end of a stick and succeeded in getting it so well stuck that it was useless from then on. No matter. The book still was interesting.

But a few Christmases stick out in my memory in more complete detail.

1949

At least I think it was 1949. It was after we moved from the apartment above Foster’s to the old house across from Grandpap and Grandma Heacox. The only thing I really wanted that year was a new bike. The one I had was a hand-me-down that went back to my cousins, Nancy and Rhoda, who were several years older than I. It wasn’t that the bike was old. Most of my friends had old bikes. But it was a girl’s bike, for heaven’s sake. Besides, Judy needed a bike and a hand-me-down girl’s bike would be ok for her. (A few years later, Judy got even when she got a beautiful red “English” bike, a three-speed a distinct rarity in those days.) So, a few days before Christmas, we were shopping in Latrobe. I happened to know that the bike shop on Main Street had exactly the bike I wanted. I begged and pleaded until Mom and Dad agreed to let me show them the bike. We walked into the store and there it was: a classic fat-tired Schwinn, green and cream in color, with a horn in the tank between the crossbars and wide steer-horn handlebars. I thought it was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen. I bent down to check the price, but then I saw the red “sold” tag and my heart fell. Someone else would get my bike. For some reason, I turned the tag over and saw “Harry Heacox!” Sure enough, on Christmas morning, there it was in the kitchen, all bright and shiny. I couldn’t wait to ride it. Of course, it was much too big for me, so I had to ride it standing up, shifting my body back and forth across the crossbar in order to reach the pedals. It would be another year or so before I was big enough to ride it sitting down. The fat-tired Schwinn was the pickup truck of bicycles. Those tires allowed you to ride up and down over 5-inch curbs without damaging either tire or rim. The wide steer-horn handlebars would hold a couple of hanging baseball gloves, along with at least two bats, with handles under one side and barrels over the other. It would easily carry a friend on the crossbar and maybe one standing on the rear axle bolts. It carried me all over town and, sometimes, out of town. It was still in Grandma’s cellar when I went away to college. Eventually, she gave it to a cousin who needed one.

There was one other Christmas custom. In mid-December, we kids would gather in the Oddfellows Hall (a fraternal organization) for the annual cartoon show. This was presented, free of charge, by Paul Amend, the father of Uncle Duck's wife, Emma Blanche. He had a collection of 16-mm films, including a number of cartoons. The Lions Club would distribute bags containing an orange, a popcorn ball, and various candies. In later years, when Paul felt he couldn't do it any longer, the tradition was carried on by Fred Piper, who owned the Gem Theater.

1953

I remember this Christmas more than most. I was old enough to be reasonably observant and this was the first Christmas after Mom and Dad split up, so everything had changed. I don’t guarantee that all the events happened that year, or in the order presented. Things tend to blur a bit after nearly fifty years. But this story is pretty representative of those years.

Thanksgiving had come and gone, which was more than I could say for the turkey. As usual, Pap had searched for, and found, the biggest turkey in town. Even the presence of Uncle Bill and Aunt Claire had not been enough to dispatch that bird. So we had drifted down through warmed-over turkey and stuffing to turkey pot pie to turkey sandwiches and finally to the inevitable turkey soup. Grandma was cooking it when I got home from school, and even I had to admit it smelled delicious. Mom wasn’t home from work yet, nor was Pap, so there was time to kill before supper. I turned on the radio just in time to hear Bing singing “White Christmas” yet again. How was it that song seemed to be playing every time the radio was turned on?

Mom finally got home from work and we set about helping Grandma put dinner on the table. While we were carrying plates and silverware, Mom and I started our annual debate about when I could start to put up my prized Lionel train layout for Christmas. Considering that it would take up a four foot by eight foot space in our living room and would probably stay there until February or March, she had good reason to put it off as long as possible. But, as usual, she soon gave in and agreed that I could work on it evenings after my homework was done.

The train was erected on a platform made of a 4x8 sheet of plywood, hinged in the middle. It sat on a frame of 2x2’s, which rested, in turn, on 12-inch lengths of pipe. This gave just enough clearance for me to wriggle underneath and run the wires to the various pieces of equipment. Uncle Roy, Pap’s brother, had helped me build the platform. I had been accumulating equipment since I was eight years old and had quite a bit. There were two pairs of switches, enough to make two independent loops and a couple of spurs. I had a station, with two baggage carts that ran endlessly around an oval track on the platform, a log dump car and a loader, a coal dump car and a loader, and a milk car with a man inside who, at the push of a button, would deliver milk cans to a platform. I had several plastic houses and a church. In addition, there were a few buildings, including a factory, that I had made from orange crates, corrugated cardboard, and various scraps. I had fashioned a few trees from steel wires twisted together, then spread apart to make branches. The twisted part was covered with plaster and painted to form the trunks. The branches were covered with lichen to make the foliage. There was even a hand-made control panel on which all the switches and controls were mounted. That train was really something. It always took me several days to set it up and get everything just right. But then, oh, the fun I had running it. That’s why I always begged to leave it up “just a little longer.” And why my mother usually gave in.

Meanwhile, at school, decorating for Christmas had started. Yes, in those days, schools actually celebrated Christmas. In our school, that meant, among other things, Christmas scenes on all the blackboards. When we were in grade school, the pictures were pretty simple and were colored in Tempera paints. As we got older, the pictures became more sophisticated and, in fifth grade, we graduated to colored chalk. The chalk made for much more subtle, realistic coloring. This year’s main scene was a country village on Christmas Eve, complete with church, horse-drawn sleighs, and lots of people. But whether the scene was simple or complex, Tempera or chalk, I was never one of the artists. We discovered early that the only thing worse than my drawing was my writing. The act of making marks on paper, or any medium, for that matter, proved to be too difficult for me. It’s still true today. Oh, I could use drafting tools to draw a pretty good schematic diagram or blueprint, but one was hard-pressed to tell the difference between the people and the horses in my drawings. So I had to be content with watching the others, mostly girls, create this year’s masterpiece.

The annual Christmas program was another feature of Christmas in schools of that time. One of the advantages of being in eighth grade was that we were in the high school building and were allowed to attend the high school program. It featured the usual selection of carols and other Christmas songs, presented by the mixed chorus. There was a singing contest among the various classes, plus several dramatic readings. The highlight, as usual, was a dramatic reading of “The Littlest Angel.” After the program, we exchanged gifts in our homerooms, having drawn names the previous week. That year, Tom Barnhart gave me a football game. It was played using dice and a look-up chart to determine the fate of each play. It was a simple-minded game, but I enjoyed it for quite a while, until the play chart was lost. For some reason, I remember walking home with it through a wind-driven snowfall.

For a thirteen-year-old boy in Western Pennsylvania in the early fifties, Christmas could be pretty iffy financially, especially this year, since Mom and Dad had separated. Anyway, my sole source of income derived from sitting in my grandfather’s barber shop each day during lunch hour, saying things like “Mr. Jones, Pap’s gone to lunch. He’ll be back in a few minutes, so why don’t you have a seat and wait for him?” Through all of this, I, of course, was sitting in the barber chair, swiveling around in circles. The barber chair was nicely padded, and much to be preferred over the wooden bench along the opposite wall. For this strenuous duty, Pap paid me the princely sum of $1.50 per week (up from $1.00 when I started the job at age 6). Oh, I forgot to mention the (usually) daily bonus – a nickel for a candy bar from Vitale’s store across the street. In any event, my income was a magnificent $78 per year, much of which I saved regularly, the object being to buy some new piece for my train at Christmas time. This year it was a brand-new diesel switcher from Reed’s department store in Latrobe. The price was a whopping $25.

After buying my prized locomotive, I had money left for gifts for Mom, Judy, Grandma, and Pap. Well, a mid-December Saturday found me on the Chestnut Ridge bus, headed for Latrobe, which was about as far as my shopping expeditions normally took me. It was a typical December day. It had snowed Wednesday, but in the land where factories belched black smoke and even blacker cinders provided traction on slippery roads, snow never stayed white for very long. Anything within thirty feet of the road was a uniform dark gray, and even the fields away from the road seemed to be a serious shade of off-white. Of course, the solid bank of clouds, which looked almost close enough to touch, did nothing to brighten the scene. Still, I had money in my pocket and Latrobe was a fine place at Christmas time. The city had decorated each and every street light with illuminated ornaments embedded in greenery. The merchants’ windows were gaily decorated for the season, and many of the stores had loudspeakers above the door, playing Christmas music for the shoppers. So my progress down Ligonier street went from the shoe store (The First Noel) to the clothing store (Silent Night) to the jeweler’s (The Christmas Song) and finally to Reed’s (White Christmas). First, I had to check Reed’s toy department. They had a huge display layout of Lionel trains, and I could spend hours watching them run. But not today! A few minutes would have to suffice. I had shopping to do.

Clearly, Reed’s was not the place for this part of my expedition. Prices here were much too high. I had just a few dollars to spend, so Murphy’s 5 and 10 had to be my next stop. But caution was needed, lest I run into my mother, who worked there. First stop was the jewelry department, where I found a fine necklace of genuine simulated pearls for my sister. In rapid succession came two handkerchiefs for Grandma and a money clip for Pap. That left Mom, but what could I get her? Nothing in Murphy’s would do, so back to Reed’s I went. Finally, I found a blue silk scarf that was just the thing for Mom. I was mighty pleased with myself as I headed back to Murphy’s, because I still had money left for one more thing for the train. I had seen rolls of “mountain paper,” paper colored a splotchy green and brown and dusted with glittering artificial snow. The idea was that it could be crumpled and attached to suitable supports, creating mountain scenery. I was eager to try such an easy method.

When I got home, I put the bag full of gifts in the big closet in Mom’s room. That was some closet for a small apartment! It was about eight feet deep, with two large shelves in the back and a bar for clothes across the front. The train was kept there, along with the decorations for the tree. It was also the storage place for Christmas gifts, until it was time to wrap them. It was an unwritten rule in the family that no one should peek at the Christmas gifts. Believe it or not, we didn’t. To me, the best thing about Christmas was the anticipation. Christmas itself always seemed to be over in a heartbeat on Christmas morning. Waiting for Christmas, shopping in stores decorated for the season, listening to the music, wondering what we’d get, all were just as much fun and lasted a whole month. Why ruin it ahead of time?

Anyway, I quickly unrolled my mountain paper, dusting the floor with artificial snow. No problem. I could run the sweeper before Mom got home. The instructions said to dampen the back of the paper with a sponge, then crumple it, straighten it out and arrange it. I had cut some supports, including a tunnel opening, from a cardboard box, so I was ready. Sponge the back. Crumple the paper (in the process depositing even more glitter on the rug). Straighten it out. Arrange it on the cardboard supports. Presto, it looked just like crumpled paper colored with splotches of green and brown paint. I tried again and yet again, but no matter what I did, there was no way to make it look like a mountain. Sadly, I kissed my 98 cents and the mountain goodbye. Now for all that glitter on the floor.

Sunday, it was time to

find a Christmas tree. That year, for the first time, we could shop for a tree

indoors, at what used to be Kist’s variety store on the corner near Pap’s

barber shop. Mr. Kist had died earlier that year and the building had stood

empty ever since. So off we went, Mom, Judy, and I. Mom liked the scotch pines

that had become popular in recent years. I hated them because of the stiff,

sharp needles. With Dad gone, it was my job to haul it up the stairs, set it up

in the stand and haul it back down again after Christmas. Each time, there were

so many needle pricks on my arms that it looked as though I had a rash. But, as

always Mom won, and I trudged away with yet another scotch pine. Now my mother

is a wonderful woman, but she could never pick a straight tree and this year

was no exception. When I got the tree up to the apartment, trimmed it to

height, and installed it in its stand, I discovered that the trunk looked like

a letter S and that there were enough gaps that I couldn’t avoid having at

least one showing.

Well, the first order of business was to straighten the tree. I quickly

realized that I couldn’t straighten it completely just by adjusting the four

bolts that held it in the stand. So I had to resort to blocks of wood under the

legs of the stand. A sheet would cover them after the tree was trimmed, so that

was OK. What wasn’t OK was the fact that the tree now was unstable and likely

to fall. That forced me to install pieces of green string tied to the trunk and

to screw eyes mounted in the baseboard. (Since we almost always needed them, we

never removed the screw eyes.) There! That would keep it steady. Now for the

gaps. I borrowed Pap’s drill and his largest bit. I drilled holes in the trunk

and inserted branches that had been cut off in trimming the tree to height.

Mom’s nod of approval let me know that the tree now was acceptable, and she and

I set about trimming it, with occasional help from Judy, who disliked the task.

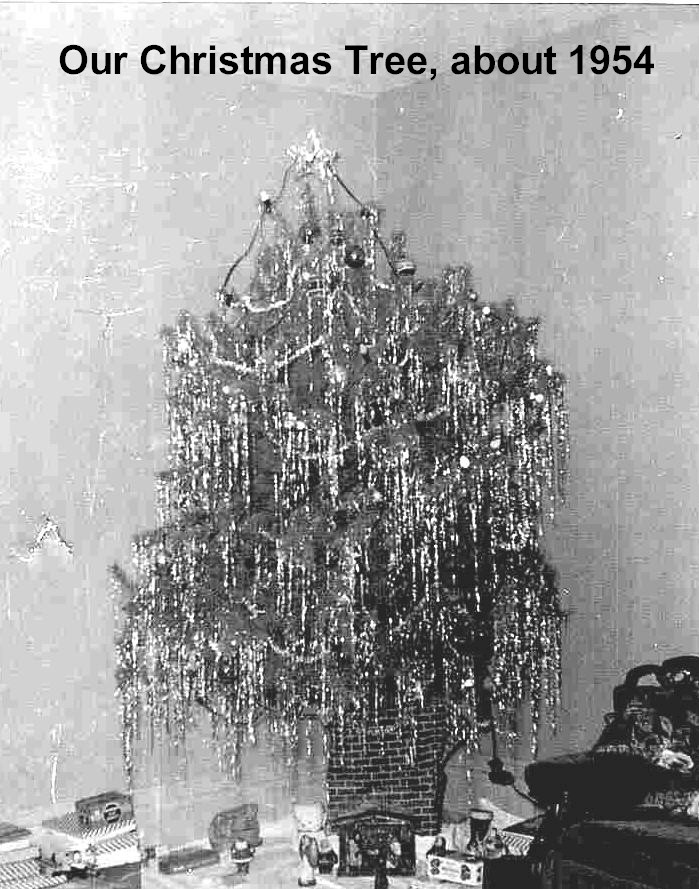

The last step, of course, was to add the icicles. That was when we had to keep

an eye on Judy. She had a tendency to get mad and sort of throw them at the

tree when no one was looking. But finally, it was done and we were just about

ready for Christmas.

Sunday, it was time to

find a Christmas tree. That year, for the first time, we could shop for a tree

indoors, at what used to be Kist’s variety store on the corner near Pap’s

barber shop. Mr. Kist had died earlier that year and the building had stood

empty ever since. So off we went, Mom, Judy, and I. Mom liked the scotch pines

that had become popular in recent years. I hated them because of the stiff,

sharp needles. With Dad gone, it was my job to haul it up the stairs, set it up

in the stand and haul it back down again after Christmas. Each time, there were

so many needle pricks on my arms that it looked as though I had a rash. But, as

always Mom won, and I trudged away with yet another scotch pine. Now my mother

is a wonderful woman, but she could never pick a straight tree and this year

was no exception. When I got the tree up to the apartment, trimmed it to

height, and installed it in its stand, I discovered that the trunk looked like

a letter S and that there were enough gaps that I couldn’t avoid having at

least one showing.

Well, the first order of business was to straighten the tree. I quickly

realized that I couldn’t straighten it completely just by adjusting the four

bolts that held it in the stand. So I had to resort to blocks of wood under the

legs of the stand. A sheet would cover them after the tree was trimmed, so that

was OK. What wasn’t OK was the fact that the tree now was unstable and likely

to fall. That forced me to install pieces of green string tied to the trunk and

to screw eyes mounted in the baseboard. (Since we almost always needed them, we

never removed the screw eyes.) There! That would keep it steady. Now for the

gaps. I borrowed Pap’s drill and his largest bit. I drilled holes in the trunk

and inserted branches that had been cut off in trimming the tree to height.

Mom’s nod of approval let me know that the tree now was acceptable, and she and

I set about trimming it, with occasional help from Judy, who disliked the task.

The last step, of course, was to add the icicles. That was when we had to keep

an eye on Judy. She had a tendency to get mad and sort of throw them at the

tree when no one was looking. But finally, it was done and we were just about

ready for Christmas.

The day before Christmas, the stores in Latrobe closed at two, so Mom was home early. We had supper with Pap and Grandma, then got ready for the candlelight service at the Methodist church. The church was brightly lit and decorated for Christmas and we were all smiles as we wished each other “Merry Christmas.” We sang the usual Christmas Eve carols, “It Came Upon the Midnight Clear,” “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” and “Away in a Manger.” As always, at the end of the service, the candles were lit, the lights were dimmed, and we sang “Silent Night.” When I think of church on Christmas Eve, that’s always the first thought.

After church, Pap and Grandma went home and so did we. We stopped in to see Millie and Pup and wish them a Merry Christmas, and stayed a while for cookies and milk. Finally, we were back home, just the three of us, and it was time to put some Christmas music on the radio and wrap gifts. For some reason, we always waited until Christmas Eve to wrap gifts and put them under the tree. Some years, the job wasn’t done until well past midnight. We split up at this point, Judy in the living room, I in my bedroom, and Mom in hers while we did the wrapping. There was a lot of yelling back and forth, and cries of “Don’t come in here yet!” But finally the job was done. Sure enough, it was after midnight and Judy, who had just turned eleven, was well past her bedtime. So, with a “Merry Christmas,” we all turned in.

Christmas morning, we were awake early, in spite of the late night. After all, there were presents to be opened. From Mom, I got a new shirt, a pair of slacks, a sweater, and not one, but two, Zane Grey western novels. (Having outgrown the Hardy Boys and Tom Swift, I had started reading my parents’ books a few months earlier.) Judy gave me a new pair of gloves. Judy also got a new sweater and a blouse, along with a new doll for her collection and a couple of books. Our stockings held the usual assortment of candy canes, tangerines, and oranges.

The morning was clear and cold as we made our way to Pap and Grandma’s house. Their tree was brightly lit. In those days, tree lights were big, mostly the size of today's night-light bulbs. There were other sets a bit smaller or a bit larger, but the night-light size was most common. Beneath the tree, as always, was the old electric train, the mirror that served as a pond, upon which various figures “skated,” the doll's house, and the two big dolls sitting in their chairs. The dolls were drastically out of scale with the rest of the scene, but no one cared. It would have been very bad manners to even suggest such a thing. Above the wide doorway between the living and dining rooms there were two banners. They were of individual cardboard letters, made to look like lengths of red twigs, tacked together. The letters were attached to one another with pins. The one facing the living room said “Merry Christmas,” the one facing the dining room said “Happy New Year.” They were Grandma’s favorite Christmas decorations, though no one knew why. The turkey was cooking in the big electric roaster and I could smell it already. We all gathered in the living room to open our gifts. The one I remember was a trackside signal for the train, with lights that turned red as the train went by, then back to green when it was safely past.

I had brought one of my new books, so I settled down on the floor between the couch and the French doors that led to the hall. With Christmas music playing softly on the old radio next to me, I began to read. An hour or so later, I reluctantly put down my book as Uncle Bill and Aunt Claire arrived. Aunt Claire was Grandma’s sister. They had no children and usually spent holidays with us. Uncle Bill was from Texas and could spin quite a yarn, or at least I thought so at the ripe old age of thirteen. Pap had outdone himself once again, with another 22-pound turkey, but he and I finally managed to get it out of the roaster and onto a platter so that he could carve it. Then we all crowded around the table in the dining room as Grandma “lifted” the dinner and brought it to the table. To complement the turkey, we had stuffing, mashed potatoes, gravy, candied sweet potatoes, corn, and 24-hour salad. In addition to the white and dark meat, Judy got the liver, I the heart, Grandma the gizzard, and Pap the neck, all according to long-standing tradition for such occasions. Conversation around the table was mainly among the adults, but Uncle Bill spent some time teasing Judy and me. Christmas dinner ended, as it always did, with pie – pumpkin, chocolate (for Judy), and coconut cream (for me).

After dinner, Mom, Grandma, and Aunt Claire began to clear away the dishes. Men and children were exempt. This last was a matter of practicality, since Grandma’s tiny kitchen couldn’t accommodate more than three workers at a time. Amid complaints of having eaten too much, Pap sprawled on the couch and Uncle Bill in the easy chair. Within minutes, both of them were sound asleep. Judy joined the women, trying to stay out of the way. That left me free to read my book in peace and take a short nap.

About 6:30 Mom and Grandma set out a supper of cold turkey, sandwich fixings, 24-hour salad, and pie. By the end of the day, we seven people had managed to eat the equivalent of three whole pies, leaving only three pieces of chocolate, two of pumpkin and one of coconut. By 9:00 Uncle Bill and Aunt Claire were on their way home, a ninety-minute drive to the far side of Pittsburgh. Shortly after, we too headed home. Once again, Christmas had come and gone, seemingly in the blink of an eye.

1956

Fast-forward three years to Christmas, 1956. Not much had changed. I was sixteen that year, and the train wasn’t as important as it had been in the past. It still was there in its corner of the living room, but it didn’t get as much use. There was a new concern that year — wheels. To be precise, Millie and Pup had decided to sell their yellow and white 1953 Chevy Belair, with the white vinyl interior. I wanted that car with a great passion and had almost convinced myself that Mom would buy it for me for Christmas. Now you have to understand that we still were living in the same two-bedroom apartment, that Mom still worked at the five and dime in Latrobe, that our rent still consumed more than half her pay, and that we still ate most of our meals with Pap and Grandma. It should have been obvious that Mom couldn’t afford even a couple of hundred dollars for a car, much less the cost of insurance. I was working for John Gruebel’s father at his Valley Dairy Restaurant in Latrobe, making the magnificent sum of fifty cents per hour, so gas money also would have been pretty chancy. Still, logic isn’t exactly one of the strong points in the mind of the average sixteen-year-old boy, so I had high hopes as Christmas approached.

Christmas Eve went along the way it usually did, ending with wrapping the last of the gifts about 1 AM. As we put the packages under the tree, one of them caught my eye. It was a couple of inches long, about an inch wide, and three quarters of an inch high. I remember thinking, “My gosh, that’s just the right size for a car key!” Well, I’ll tell you I had a bit of trouble getting to sleep, thinking about that little package. Christmas morning finally came, and we gathered around the tree to open gifts. A nice shirt, a book, the usual stuff. All along I had my eye on “the package,” saving it for last, anticipating. Finally, it was the only one left. I ripped it open to find — a nice, shiny tie bar. Mom never knew.

1957

One more Christmas. In 1957, I was seventeen and a high school senior. Christmas had been pretty much the same most of my life, except for the effects of Mom and Dad separating, and that had just about healed. But this year, I was looking ahead to college and I knew that things would change. I didn’t know how soon. I had been dating Barb, my first real girl friend, for about a month and my Christmas trip to Latrobe had a special purpose – a gift for her. I was working after school at the A&P supermarket and making the huge sum of $1.53½ per hour, so I had a little money to spend. The big thing that year was the identification bracelet and I was determined to get one for Barb. I shopped at all the jewelry stores, finally finding one in 14K gold for less than ten dollars. That I could afford!

In our house, music was nearly an obsession. Some of my earliest memories are of records by the King Cole Trio or Glenn Miller playing on the old Philco console. It was the size of a small chest of drawers, with a radio in the top part, its dial glowing brightly. In the bottom part was a single, enormous speaker. In between were two doors that concealed a 78-rpm phonograph with record changer. It got a good workout. However, by the fifties, 78s were pretty much obsolete, replaced by 45- and 33-rpm records. In 1955, Dad had given us a TV-radio-phonograph console, a good one. Unfortunately, after a few months it was repossessed because he couldn’t make the payments. A couple of months after that, he talked another store into selling him a table model with a blonde wood cabinet. Predictably, that one, too, was repossessed after a few weeks. So this year, Mom, Judy, and I decided to buy our own as a family gift. It was to be the only gift we’d buy. We found a Voice of Music “portable” (that meant it had a handle and could be carried by a fairly strong person) at Edsall’s appliance store, two doors down from our apartment. That phonograph served us well for a long time. It even provided the music for several dances of the local chapter of the Catholic Daughters of America (Barb was president that year).

About a week before Christmas, Barb asked me if I would go to midnight mass with her on Christmas Eve. Now you have to understand how such things were viewed in Derry in the fifties. Most of my friends had names like McManamy, Rondinella, and Kozemczak. Catholics. Certainly, it was OK to have Catholic friends (actually, it was almost impossible not to), but to go to the Catholic Church! Well, that was strike one. Strike two was the fact that our little family had always spent Christmas Eve together. We used our closeness as a shield against the fact that Dad had left us. We huddled together as our defense against the world. And now I wanted to leave that shelter before I had to, just to go to the Catholic Church with my girl friend. Well, when you’re seventeen and in love, what else would you do? Mom and I had several talks, some of which might be called arguments. But in the end she relented, and off I went with Barb. I remember little of the service, except that there seemed to be a lot of kneeling. After church, we went to Sandy Fisher’s house for a little party — music, potato chips, Pepsi, and a few kisses in the corner. I got home about one o’clock to find Mom still up, as I expected. We talked a while, then went to bed. By the time we got up Christmas morning, things seemed quite normal. It wasn’t until years later that I understood that I really started leaving home that Christmas Eve.